I wrote a book called Home Computers

April 19, 2020 ・ Blog

I wrote another book! This time about a bunch of computers, and it came out last week. What a time for a book launch. Gah, let’s not think about that!

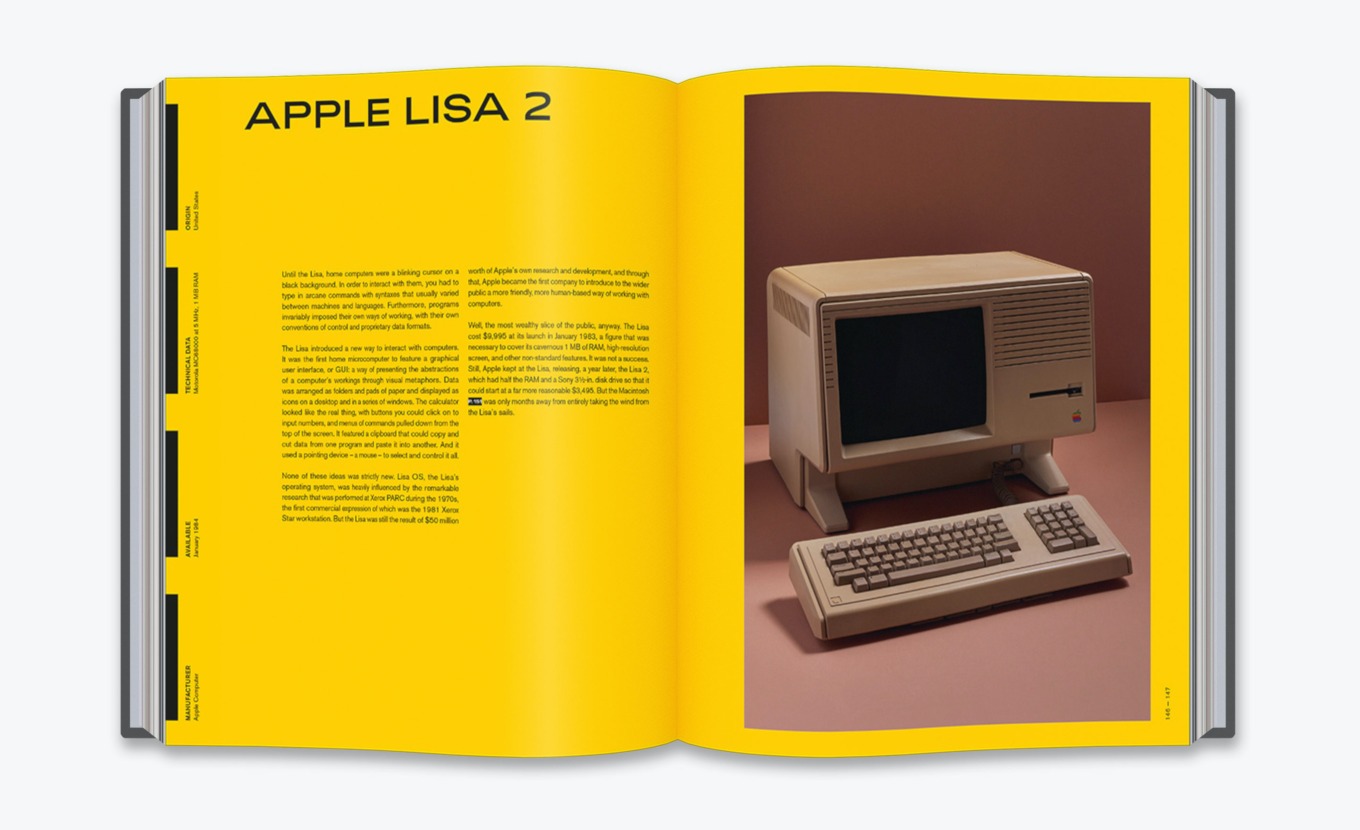

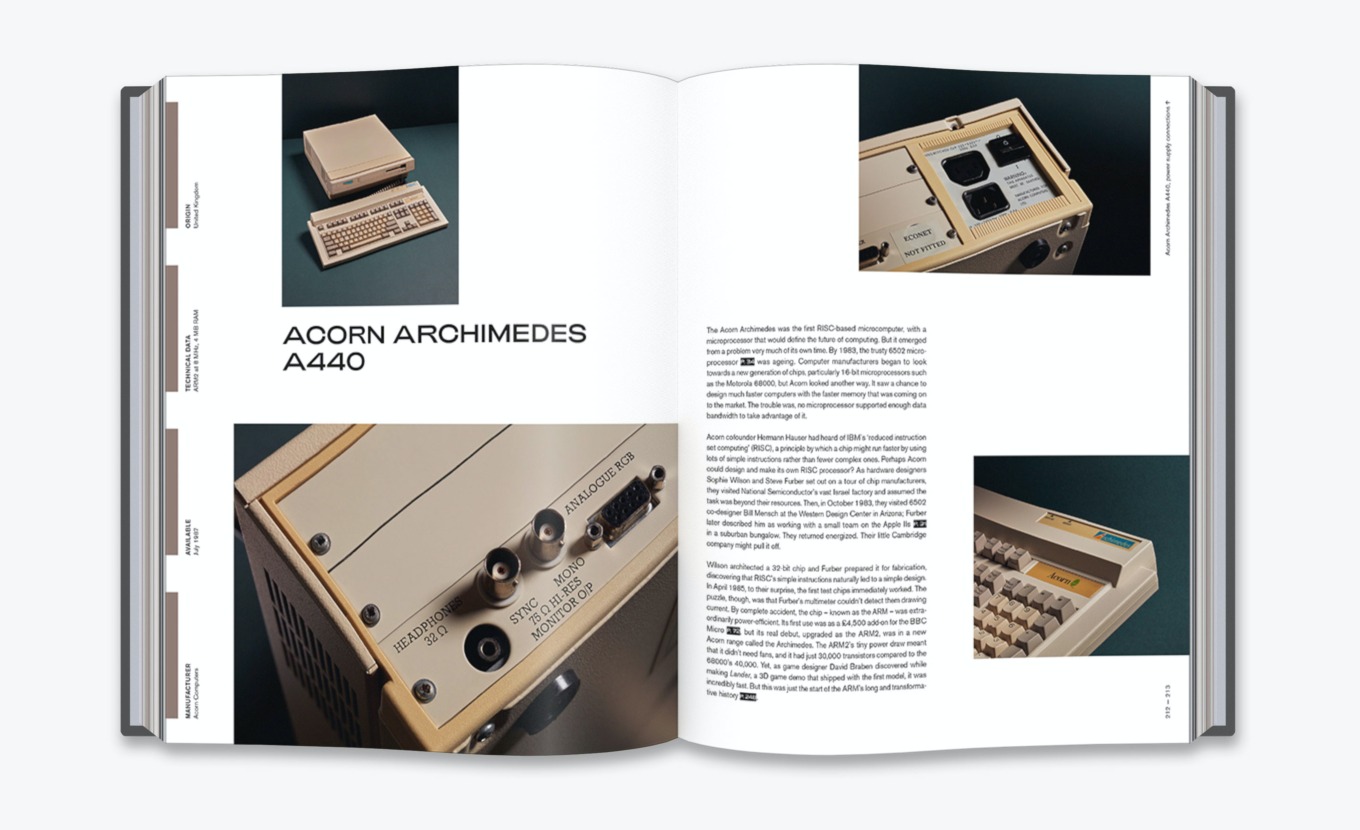

It’s called Home Computers: 100 Icons that Defined a Digital Generation, and it collects 100 machines which tell the story of the rise of the home computer, from the kits of the 1960s to the off-the-shelf all-in-ones of the late 1970s; their entry into living rooms and bedrooms in the 1980s; and then taking a role in everyday life into the late 1990s.

Home Computers was conceived and managed by Darren Wall, who had visited the Centre for Computing History and thought of picking out 100 computers from its collection and photographing them in a way which emphasises their physicality, keyboards, tape covers, backplates and all.

The fantastic photography is by John Short. It evokes the rich look of 1980s advertising, but also celebrates the blemishes the computers picked up over their lives. The Observer published a gallery of some of it last weekend.

These objects are known for what they displayed on screens, but their cases give a strong sense of what place they took in homes and on desks and in garages. As you go through the book, you see how a design language formed around their interior electronics.

The design is by Johanne Lian Olsen, which hints at the classic modernist look of 1960s and 70s, confident and bold, but also characterful.

It was fun to write. Every entry was a window into a time of constant and massive change, particularly during the tumult of the early 1980s, when computers and companies would come and go in a matter of months. I knew some of the stories, but I learned many more, about East Berlin computer clubs, Claude Shannon, fraud in Hong Kong, Soviet Spectrum clones, failures and disasters, successes and fortunes, personalities and corporations.

I’m trying to resist nostalgia for it all, because looking at them today, the early days of the home computer seem so dynamic and full of possibility; almost innocent. That’s not true, of course. But what I do miss is that time’s sense of the personal: a computer was yours to own and tinker with and learn from. It wasn’t ubiquitous; it was a choice, and it didn’t tell you what it was for.

I suppose that makes it an elitist time, too. And that tension – between tech utopianism and capitalist commercialism and social progressivism – I think that’s what I find so fascinating.